I want to reiterate that one of the neat things about researching history and then putting the findings into a book means that more discoveries are usually right around the corner for the author. With the arrival of the internet it is easy for somebody to read a book and then realize they have something pertinent that would be of interest to the author. This has happened to me several times over the years and it occurred again when I received an email from Dave Walker on the west coast after he had purchased a copy of The Confederate Alamo. He had heard about the Battle of Fort Gregg in 1865 and knew that one of his relatives Lieutenant James E. Northrup, 89th New York Infantry Regiment, had participated in the bloody attack against the handful of Rebels who manned the fort. These Southerners had earlier received an order from General Lee “to hold at all costs.”

The first wave of Union attackers raced across 800 yards of open ground in the face of withering small arms and cannon fire. Those not shot down discovered a big problem as they approached the fourteen foot high earthen wall – a water-filled moat guarded the base of the wall. This initial attack bogged down and reinforcements raced to the rescue. Northrup’s 89th New York and a sister regiment, the 158th New York, joined the second attack wave. By the time these New Yorkers reached the scene and waded through the dead bodies in the moat they had lost a number of their own men including most of the color-bearers and Major Frank Tremain, the young commander for the 89th.

The first wave of Union attackers raced across 800 yards of open ground in the face of withering small arms and cannon fire. Those not shot down discovered a big problem as they approached the fourteen foot high earthen wall – a water-filled moat guarded the base of the wall. This initial attack bogged down and reinforcements raced to the rescue. Northrup’s 89th New York and a sister regiment, the 158th New York, joined the second attack wave. By the time these New Yorkers reached the scene and waded through the dead bodies in the moat they had lost a number of their own men including most of the color-bearers and Major Frank Tremain, the young commander for the 89th.

After another hour of bitter fighting, much of it hand-to-hand, Union troops rolled over the fort’s walls and smashed through the wooden sally-port. The end was near for the Rebel garrison that was now out of ammo, men and hope. The inside of the fort was likened to the smoking cauldron of Hell. Amidst this chaos the senior Confederate officer, Lieutenant Colonel James Henderson Duncan, dropped to the ground with what appeared to be a fatal head wound. An 89th New York soldier stood over Duncan’s prostrate body and raised his musket to skewer the Mississippi officer with a bayonet. Lieutenant Northrup barked out a loud order that stopped the New Yorker from committing an atrocity.

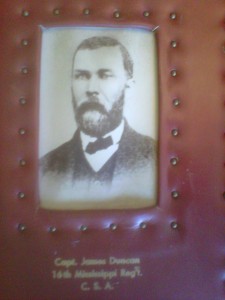

The confusion over the name Duncan came about because the senior captain in the 16th Mississippi which manned the fort was Captain James H. Duncan who was in his early thirties. The twenty-six-year-old lieutenant colonel from the 19th Mississippi who was saved by Northrup had the same name with the same middle initial. By the way, Lieutenant Colonel Duncan did survive his bloody head wound.

The confusion over the name Duncan came about because the senior captain in the 16th Mississippi which manned the fort was Captain James H. Duncan who was in his early thirties. The twenty-six-year-old lieutenant colonel from the 19th Mississippi who was saved by Northrup had the same name with the same middle initial. By the way, Lieutenant Colonel Duncan did survive his bloody head wound.

The similarity had befuddled other historians and the general consensus until recently was that the men were one and the same. Their Compiled Service Records at the National Archives are even juxtaposed together. But they are not the same. Their service together in the same Mississippi brigade fighting at the same small Confederate fort at the end of the war was a mere coincidence.

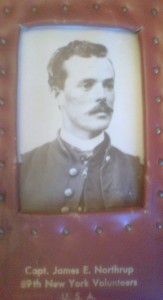

Now, imagine my interest when I received the July 2011 west coast email from the relative of Lieutenant [later Captain] James Edgar Northrup. Not only did he have a war-era photo of Captain Northrup but he also had a photo of Captain James H. Duncan – and, he also had a Colt revolver surrendered by Captain Duncan to Lieutenant Northrup. Apparently, Northrup’s family met with Captain Duncan’s family several years after the war ended but Captain Duncan had died. He is apparently buried at Culpeper, Virginia.

Adding confusion to the Fort Gregg surrender story was an old newspaper article from the Culpeper [Va.] Exponent, May 6, 1901, that included excerpts from a letter that Captain Northrup wrote to Captain R. R. Duncan, brother of Captain James H. Duncan. This article does not mention the surrender of a pistol at Fort Gregg but instead mentions the surrender of a sword. The article indicates that the sword was shipped to the Duncan family by Northrup.

Adding more confusion to the story is evidence that Captain William Smiley from the 12th West Virginia accepted the sword of surrender from Lieutenant Colonel James H. Duncan who may or may not still have been unconscious.

Adding more confusion to the story is evidence that Captain William Smiley from the 12th West Virginia accepted the sword of surrender from Lieutenant Colonel James H. Duncan who may or may not still have been unconscious.

Anybody who perhaps knows more about the confusing Confederate surrender at Fort Gregg please let us know. I do want to thank Dave Walker who is Captain Northrup’s great-great-grand nephew for sending me these great photos and adding more to the remarkable Fort Gregg story.

Dear Mr. Fox—I hope this email finds you well. I wanted to let you know how much I appreciated your work on Fort Gregg (“The Confederate Alamo”) and your follow-up blog posts on that subject, which I have just recently discovered. Lt. James E. Northrup was my great great uncle (my grandfather’s uncle and the older brother of my great grandfather). His exploits during the war (wounded at Antietam) were events I vaguely remember hearing about from my grandfather when I was a young boy. My family had an account of James’ heroism at Fort Gregg from his own diary and as contemporaneously reported by his commanding officer:

“April 2, 1865 – This morning called into line by tremendous volleys of musketry on our right…we soon were ordered out…we moved up towards Petersburg where we met the enemy in his lines. We charged on the works and after a desperate fight we took the fort (Gregg). Major Tremaine was killed; we lost heavily.”

From Brigade Commander Fairchild’s report of the capture of Fort Gregg and its resulting break in the Confederate Richmond-Petersburg line of defense and his citations for valor: “I desire to make mention of officers and men whose bravery and gallantry came under my immediate notice…Actg. Adjt. James Northrup, 89th N.Y. Volunteers, who, asking who would follow him into the fort, three privates responded and they went in together, followed by the troops of both regiments”

My grandfather would dramatize his narrative by bringing out “uncle James’” infantry officer’s sword and a wooden box filled with battlefield souvenirs (rusted needle bayonets, mini-balls) that my grandfather must have collected when he was a boy in the 1890s on a visit to some civil war battlefield, no doubt guided by James. Whether the battlefield souvenirs came from Fort Gregg or perhaps Gettysburg, since James resided in Binghamton NY after the war, I know not. Regardless, James’ sword is now in my possession and, being reenforced by your account of the battle, I will always envision James as holding this sword in his right hand as he moved forward with the “three privates,” leading the charge into Fort Gregg. Thanks for making history come alive!

Best regards,

Mark D. Northrup

(Seattle attorney, retired)