One of the things I love about researching and then writing a book about a historical event is the numerous sub-stories that evolve. Frequently a descendant of a Civil War veteran or somebody doing similar research fills me in on one of these stories.

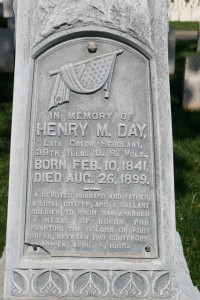

A friend of mine who travels all over the country compiling photos of Confederate general’s graves and who is also working on a photo project that includes a compilation of Confederate monuments throughout the country recently sent me some interesting photos. Bob Price from Atlanta emailed me four photos he took of Corporal Henry M. Day’s grave monument at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery at St. Louis. This is a link to Bob’s excellent work referred to above.

civilwarmonumentsofthesouth.com

Bob’s photos triggered my interest because when I was writing the manuscript for The Confederate Alamo: Bloodbath at Petersburg’s Fort Gregg on April 2, 1865, I was aware of the questions that involved what twenty-four-year-old Corporal Henry Day did in the Union charge against Fort Gregg. There seems to be no doubt that Day sprinted across the wide killing zone in front of the fort with the 39th Illinois flag staff clenched in his hands, the colors snapping above his head. Somehow he made it unscathed to the wide ditch that guarded the fort’s walls. He splashed into the water that filled this moat. He probably pushed some dead blue uniformed bodies out of the way as he slogged through the shoulder deep water to the base of the fourteen foot parapet wall. He caught his breath there in this relatively safe spot as the Rebel guns could not depress downward to fire in his direction.

The 39th Illinois was assigned to the brigade commanded by pre-war Chicago lawyer Colonel Thomas O. Osborn. Osborn’s men and Colonel George Dandy’s brigade formed the first wave to attack the half-moon Henry M. Day, grave monumentshaped earthen walls of Fort Gregg. Earlier that day, after Robert E. Lee’s outer defense line southwest of Petersburg had collapsed under pressure from the Union 6th Corps, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia had issued a suicide order – “Hold at all hazards” – to the 334 grimy Confederates who manned the fort. Thus the stage was set for the violent confrontation several hours later in which Day was a participant.

The 39th Illinois was assigned to the brigade commanded by pre-war Chicago lawyer Colonel Thomas O. Osborn. Osborn’s men and Colonel George Dandy’s brigade formed the first wave to attack the half-moon Henry M. Day, grave monumentshaped earthen walls of Fort Gregg. Earlier that day, after Robert E. Lee’s outer defense line southwest of Petersburg had collapsed under pressure from the Union 6th Corps, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia had issued a suicide order – “Hold at all hazards” – to the 334 grimy Confederates who manned the fort. Thus the stage was set for the violent confrontation several hours later in which Day was a participant.

Because of the steepness of Fort Gregg’s wall and the accurate small arms and canister fire, Osborn and Dandy’s men found themselves trapped in the moat. More blue reinforcements charged across 800-yards of open ground to aid their colleagues. After more than two hours of the ugliest fighting some 4,400 Union soldiers in five brigades clambered over the wall into the pit of the fort and overwhelmed the few unwounded Confederate defenders.

Corporal Day joined this surge to the top of the wall where he planted his Illinois colors only to be hit in the chest by some type of projectile. He dropped to the ground with a severe wound and control of the flag probably passed to Corporal Abner P. Allen. Day was evacuated to a hospital and the unwounded Corporal Allen remained with the 39th Illinois all the way to Appomattox.

Several weeks later, Allen accompanied fourteen other soldiers, most of them color bearers from other regiments involved in the Fort Gregg assault, on a trip to Washington to receive Medals of Honor from Secretary of War Edwin S. Stanton.

Corporal Day would go to his grave in 1899 at St Louis Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery certain that he was a Medal of Honor recipient too. The large monument that towers over his grave says so. The only problem is that there is no corroborating paperwork to be found that backs up Day’s award.

Did an officer promise Day this award of valor as he was carried away to a hospital? Did Corporal Allen stand-in for Day’s award? Did the Medal of Honor paperwork get lost or misplaced?

Several war books validate the claim that Day received the award. One of these was a regimental history written in 1889 by the regiment’s surgeon, Doctor Charles Clark. The other book was an 1876 account of Will County, Illinois veterans. Additionally, the Illinois Adjutant General’s report on the Civil War lists Day as a MoH recipient. Clark’s history also mentions Day’s valor but there is little mention of MoH recipient Abner Allen.

Then the 1961 panoramic painting by artist Sydney King came out. King’s brush shows the violence of the fight and right in the middle of the work stands a brave figure pushing the splintered staff of the 39th Illinois flag into the sod atop the fort’s parapet. The figure was Corporal Henry Day and the description of the painting stated that he received the MoH for his bravery in the battle. Day and his medal were even mentioned in a 1965 National Geographic article commemorating the war. The only problem was that artist King used information from the 1889 regimental history for the painting.

Several researchers through the years have scoured Day’s Compiled Service Records, but so far no MoH paperwork has surfaced. Pension records might clear up the mystery, but Day’s pension records cannot be found.

Evidence seems to exist that Day is worthy of the nation’s highest award, but until a copy of his Medal of Honor citation turns up then he cannot be officially be credited for his valor. Perhaps one day, a researcher will stumble across the missing papers. If so then it would be a fitting end to an old mystery that shrouds the service of a brave man.

Hello. I wrote the Chicago Tribune article about Henry Day. I am glad to see you added the controversy in your book, which I am enjoying reading. Researching the 39th Illinois has been a hobby of mine for years. You may be interested to know there are photos of Homer Plimpton (who appears in that Sidney King painting with raised sword) and also that he left an as yet unpublished journal from the Civil War. As to Henry Day, I still have found no documentation to go with the Medal of Honor claim. Lately I have been speculating that his paperwork got mixed up with that of Henry Martyn Day. Civil War Union Brevet Brigadier General. Served during the Civil War first as the Lieutenant Colonel of the 1st Illinois Volunteer Cavalry, then as Colonel and commander of the 91st Illinois Volunteer Infantry. He was brevetted Brigadier General, US Volunteers on March 26, 1865 for “faithful and meritorious services during the campaign against the city of Mobile and its defenses”. But perhaps that is just wishful thinking.

Charles, I apologize for taking so long to respond to this but due to technical issues I am just now seeing comments. Your Trib article was excellent and I am glad I was able to include the info in “The Confederate Alamo” because it makes for a very interesting and compelling story. Day certainly believed that he was a Medal of Honor recipient. I hope his claim will be validated one day by the appearance of the missing paperwork. do you know where the Homer Plimpton photos are and who has his unpublished manuscript? Does he reference Fort Gregg in the manuscript?

I am interested in any and all information updates as to Henry M Day’s MOH substantiation.

Tom E Summers

Great Great Grandson of Henry M Day